Community libraries are filling the gaps in India’s public library network. But what kind of impact do these facilities have on local people and society?

In many parts of India, finding a good book to read is not always easy. Take Uttar Pradesh, for example, has 200 public libraries, but these libraries are shared across 98,000 separate villages. The network is simply stretched too thinly.

This is what makes community library projects and initiatives so valuable. Extending that public library network to meet the needs of such a huge community is always going to be time-consuming and difficult. However, smaller-scale community operations can easily fill the gaps.

A Blossoming Network of Projects

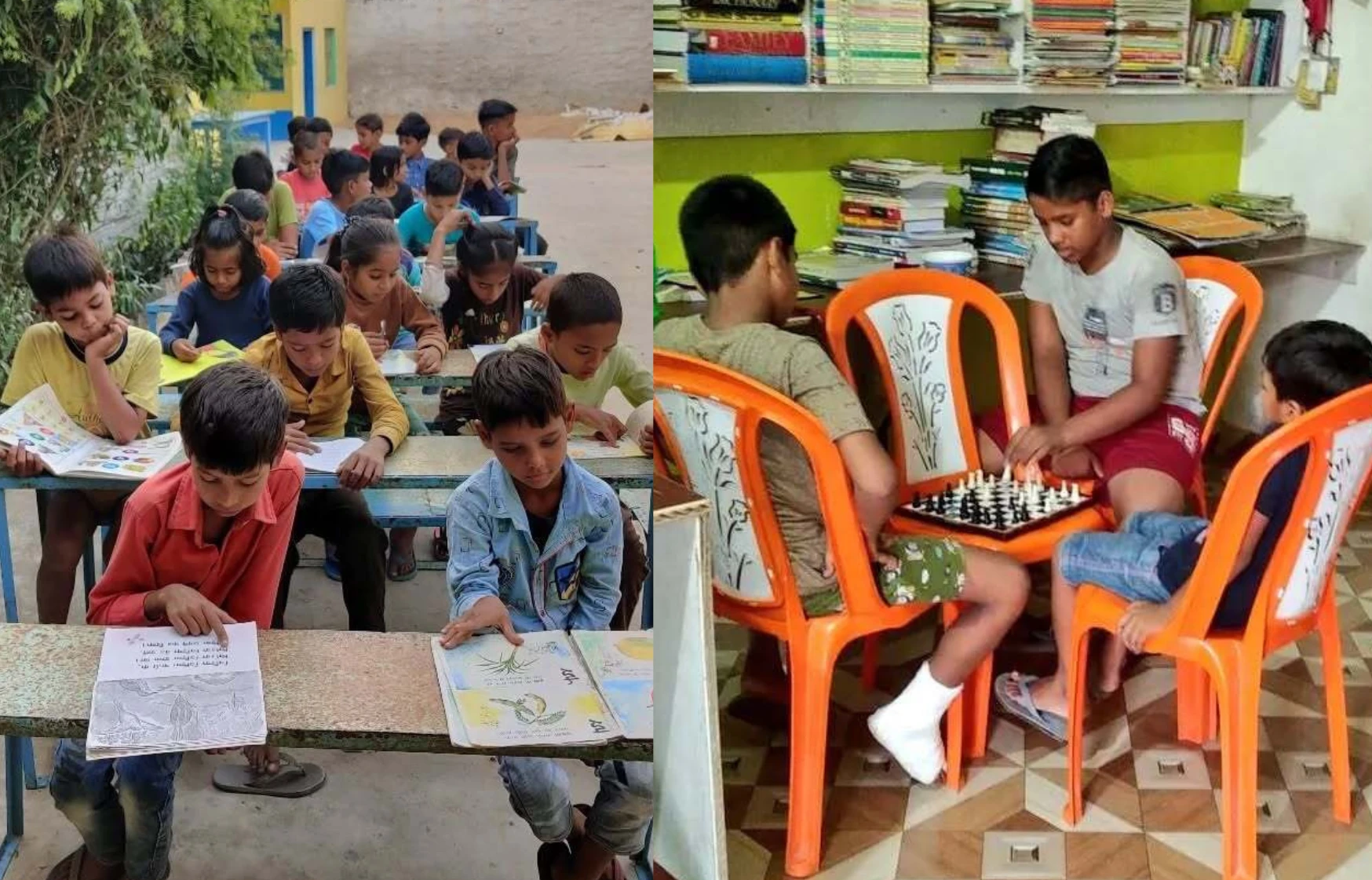

Back in 2009, the Community Library Project (TCLP) began in Delhi. Originally, this was a book club, but over time, the organizers realized that participants didn’t have easy access to books of their own, and the TCLP evolved into a free library instead. Its four branches in Delhi were providing 4,000 local children with access to books as of 2025.

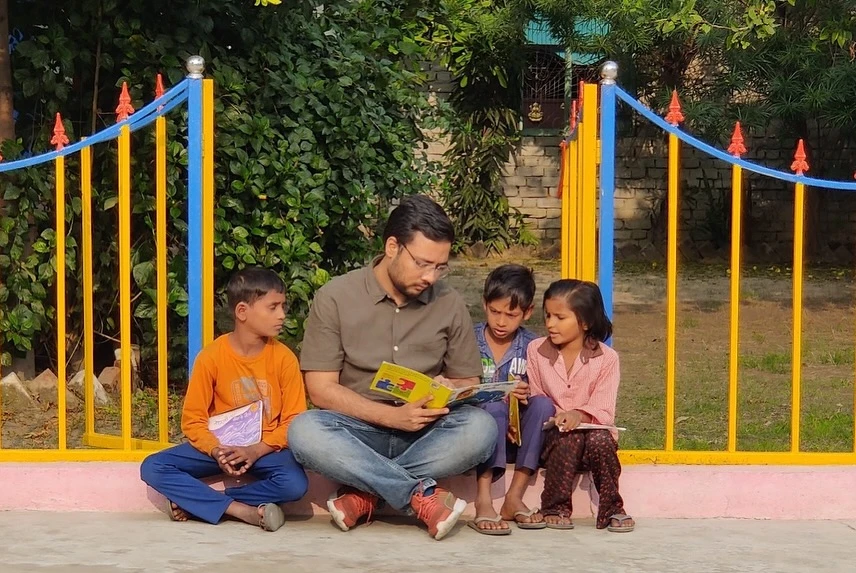

Of course this is a great project, but it’s just one in an enormous country. Inspired by the work of TCLP, other projects began to spring up in different locations across India. For example, the Buguri Community Library in Karnataka, founded in 2017, or the Bansa Community Library in Hardoi, co-founded by Jatin Lalit.

For Jatin, these community libraries are wonderful for several reasons. One, they make books accessible. Two, they are free, so community members aren’t having to choose between reading and daily essentials. And three, they remove all the red tape usually associated with libraries.

“The idea of such small community libraries is to make it as convenient as possible for people to pick up a book instead of playing with their phones,” he says. “They are free to use, open to all, and most don’t require a membership fee.”

The Beginning of the Library at Hardoi

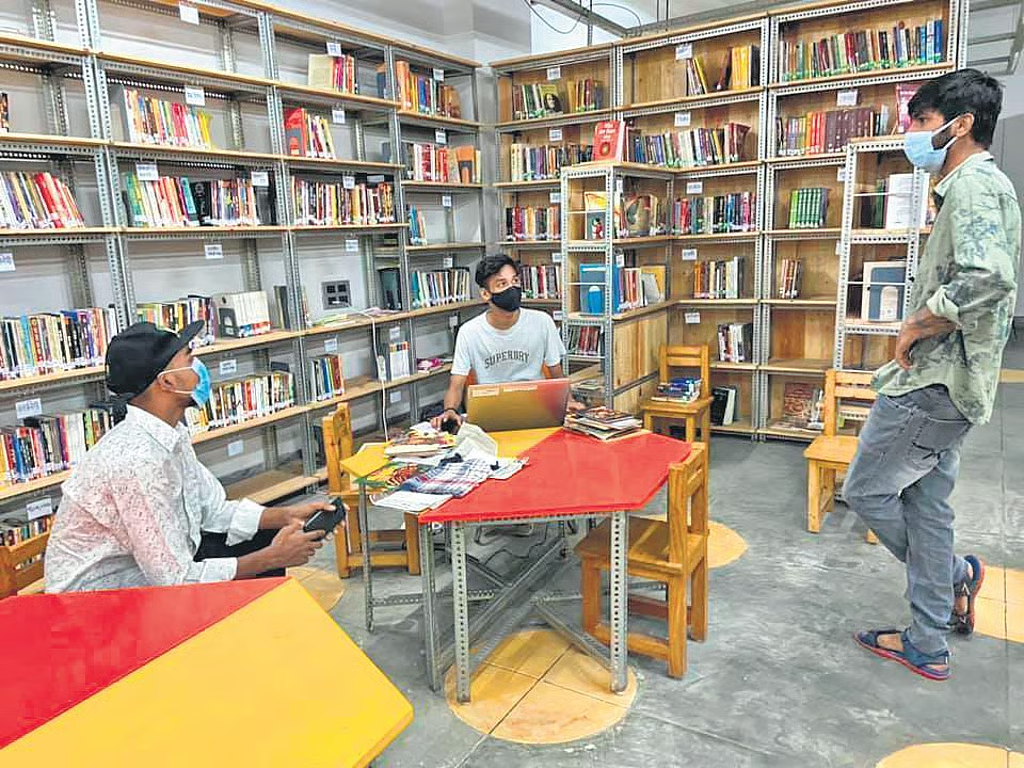

Jatin’s own Bansa Community Library began life during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. Initially, Jalit had been focused on helping stranded migrant workers make their way home, but then he realized there was something else these workers needed.

“We realized that once home, the workers had little to do, and no opportunities to better themselves,” he remembers.

“Building a free library, a community-owned safe space where they could read or study, seemed like a good idea.”

Hardoi is not a small town. More than 125,000 people call this place home. However, the location in central Uttar Pradesh, 110 km from Lucknow and 385 km from New Delhi, is underserved by local public libraries.

Uttar Pradesh, in general, struggles with literacy. Recent studies found a literacy rate of only 68.5% on average across the region, around 10% below the national average.

Jatin and his team are doing their part to improve these figures and are also working to provide valuable resources for learning, development, and enjoyment through reading. Five years after the project opened, there are more than 2,100 registered members, and the library welcomes around 100 people every day.

A Tactful Approach

Jatin and other library founders and co-founders understand that a careful, tactful approach is required. If the idea is to support literacy and to give everyone the resources they need to enjoy books and reading, libraries need to be accessible. While the lack of a membership fee certainly boosts this accessibility, there are other things to consider here.

“We never ask people who come to the Bansa Community Library to read,” Jatin says. “We leave it to our members to choose whether to read, study, play, or hone their computer skills.”

This is a really important aspect of a project like this one. In a community where more than 30% struggle with literacy, advertising a library that is all about reading is going to put many people off. Instead, Jatin and his fellow community library founders and managers focus on fun, togetherness, and acceptance.

Bringing the Benefits of a Library to the Masses

These days, Jatin Lalit has rather a lot on his plate. After helping to found the library at Hardoi, he has been practicing as a lawyer in New Delhi. In addition to this, he is the general secretary of India’s Free Libraries Network (FLN).

The FLN essentially takes the individual benefits of community libraries and transposes them into locations right across India and South Asia. From Kerala in the south, to Ladakh in the north, and from Arunachal Pradesh in the east, to the Nicobar Islands out in the Andaman Sea, the FLN’s libraries bring joy and possibility to people across a huge area.

The FLN does not create libraries itself. Instead, it provides resources, assistance, and support, fostering a growing coalition of independently run libraries across the subcontinent. This is the essence of the community library – a small, individual project, with inherent connections to the wider community.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.