Happy 91st birthday, Carl Sagan! Celebrate his genius by exploring the books that shaped his brilliant mind and lasting legacy.

Carl Sagan was known as an incredible visionary, and his legacy lives on long after his passing in 1996. Gone too soon at 62, Carl Sagan would’ve been 91 this year, and for those who wish to celebrate such a great mind, why not do so this year by reading some of Carl’s book recommendations?

Where Do These Book Recommendations Come From?

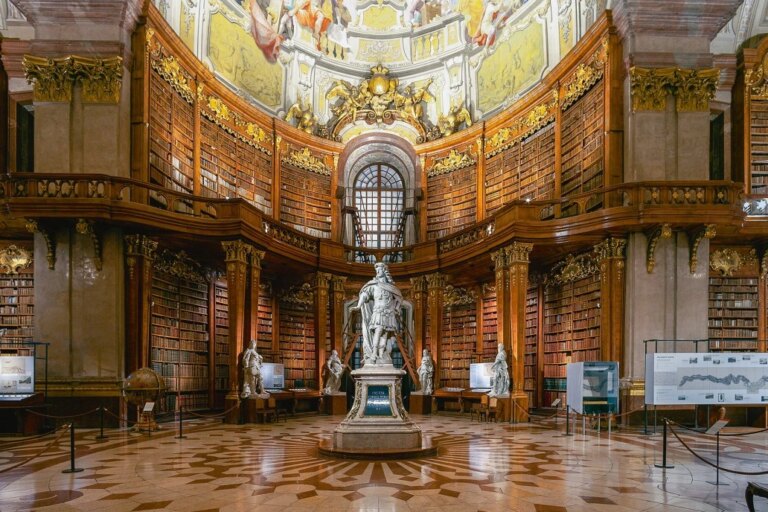

Carl Sagan was known to be a big reader; in fact, at one point, he said that “a book is proof that humans are capable of working magic.” In an essay titled The Path to Freedom, published just before he died, he lamented about books, saying that they “permit us to interrogate the past,” “to understand the point of view of others, and … to contemplate … the insights, painfully extracted from nature, of the greatest minds that ever were.”

It makes sense that he would have a large library and read plenty in his lifetime, which we have plenty of proof of. One such piece of proof is his handwritten college reading list from 1954.

Now, of course, there are a number of books on this list that are strictly course-related, and there isn’t a whole lot of fiction. It was, after all, the reading list of a man who became one of the greatest famous scientists America knew in the 20th century. Still, there are plenty of interesting things on the list, and definitely texts worth picking up if you want to understand Sagan’s mind that little bit more!

Carl Sagan’s Fiction Suggestions

There isn’t a whole lot of fiction on Carl Sagan’s 75-year-old reading list, but there are a few texts that allowed Sagan to lose himself a little. The notable fiction texts on Carl Sagan’s reading list include STAR science fiction stories, an anthology by Frederik Pohl.

It was published in 1953 and includes works by William Morrison, C. M. Kornbluth, Lester del Rey, Fritz Leiber, Clifford D. Simak, John Wyndham, William Tenn, Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Judith Merril, H. L Gold, Robert Sheckler, Henry Kuttner, Murray Leinster, and Arthur C. Clarke.

Also on the list was Young Archimedes and Other Stories by Aldous Huxley. This is a collection of six stories, considered to be somewhat autobiographical. The stories were originally published under the title “The Little Mexican and Other Stories.” The stories are set in Europe and offer thoughtful discourse on childhood, love, life, death, and society.

The Immoralist is a confessional account of a man who is seeking the truth of his own nature. Michel, the story’s protagonist, marries Marceline out of his duty, only to meet a young Arab boy on their honeymoon. He discovers a new freedom in living his own life, but also tackles the burden that comes with that freedom.

Finally, the last full-length fiction piece on Carl Sagan’s college reading list was Julius Caesar by none other than William Shakespeare. The famous play sees Jealous conspirators convincing Caesar’s friend and confidant, Brutus, to join their assassination attempt against Caesar, in the hopes of stopping him from gaining too much power.

Sagan’s Philosophies

Where there were only a few fiction titles, there were significantly more philosophical titles. It seems that Sagan valued philosophy greatly, even though it was a scientific course he was about to undertake.

Some of the philosophical titles on his list include Who Speaks for Man? by Norman Cousins, a text exploring the debate of humanity and nuclear disarmament.

He then had multiple pieces by Plato. First on the list was Symposium, a dialogue that follows a man telling a story he heard from another man about a symposium (a party). Also on the list was Timaeus, an elaborate account of the formation of the universe, and The Republic, Plato’s examination of justice, order, the city-state, and man.

Non-fiction On Sagan’s List

There were other non-fiction titles on Carl Sagan’s list, too. These were, in fact, the majority. Of the non-fiction texts on the list, there were several course-related scientific journals and textbooks, but there were also a number of other texts.

For example, Death Be Not Proud. This 1949 memoir was written by an American journalist, John Gunther. The memoir follows the decline and, ultimately, the death of Gunther’s son Johnny. Johnny suffered from a brain tumor and died an untimely death at the age of 17.

In addition to this memoir, there was a detailed account of the J. Robert Oppenheimer Security Clearance Hearing. Looking into the work of Robert Oppenheimer at the Manhattan Project and the following court case that established concern that Oppenheimer might be an “agent of the Soviet Union.”

Another interesting piece on Sagan’s reading list is Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay. The book was published in three volumes: National Delusions, Peculiar Follies, and Philosophical Delusions. Each of the books sees Mackay, a Scottish journalist, debunk alchemy, duels, fortune-telling, haunted houses, the influence of politics on the shapes of bears, prophecies, relics, and crusades.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.