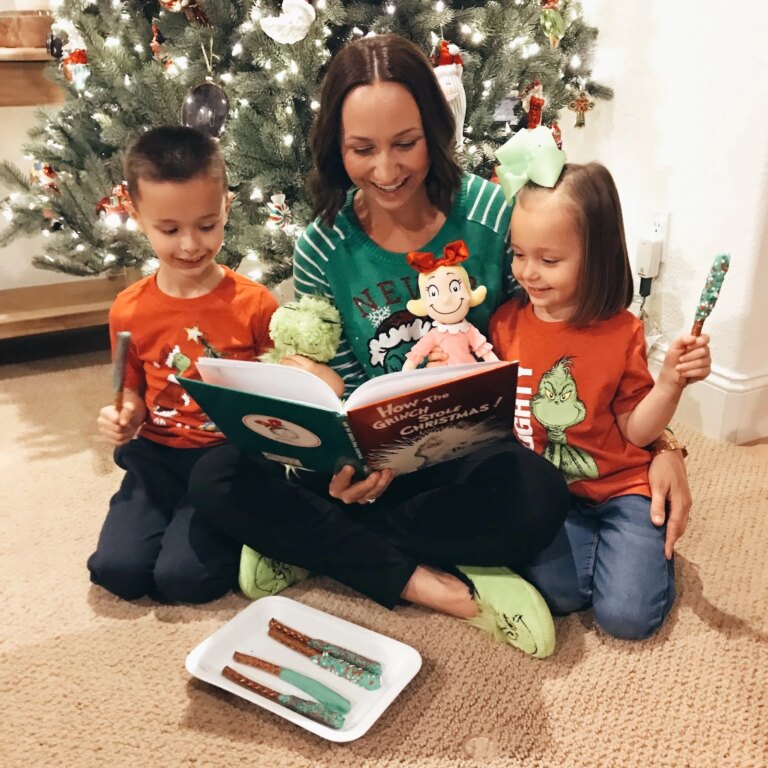

Meet Nobuo Okano, the Japanese artisan whose delicate book restorations revive fragile, battered volumes and preserve the memories they carry.

There’s something deeply satisfying about giving something old a new lease on life. Taking worn-out things, things that have been forgotten because life got busy. So when the internet came across the story of Nobuo Okano, a Japanese craftsman who restores old, battered books and turns them into near-pristine versions of themselves, everyone was hooked.

Who is Nobuo Okano?

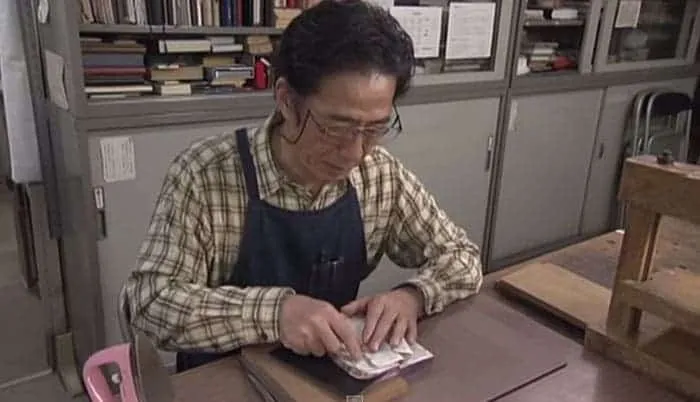

Nobuo Okano is no overnight hero. He has spent 30 years mastering the craft of book restoration. That’s three decades of preserving ink smudges, threadbare spines, dog-eared corners, and fragile maps tucked in old dictionaries. When you do something for that long, you start seeing books not simply as objects, but as stories and art combined into a physical form.

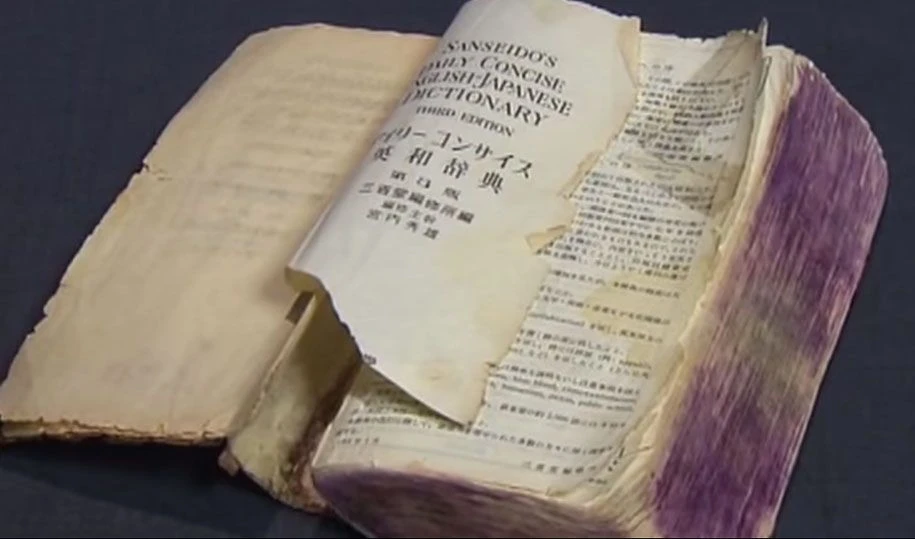

His story began with a particularly challenging project: a 1,000-page English–Japanese dictionary, which had been used years ago by its owner, then passed down through time, picked up again in a moment of nostalgia, and finally given to Okano for restoration.

What Kind of Damage Are We Talking About?

The types of books Okano takes on aren’t just a little used or dirty. We’re talking major wear and tear, things that you’d think are beyond saving. Think pages with torn or folded corners, maps inside that are discoloured, brittle, or creased.

He takes on spines where the glue has deteriorated, edges with wear or aging, and covers that have faded, sometimes even losing the title completely. Some of the books look like they’ve already lived several lifetimes.

The Restoration Process: It’s Like Surgery

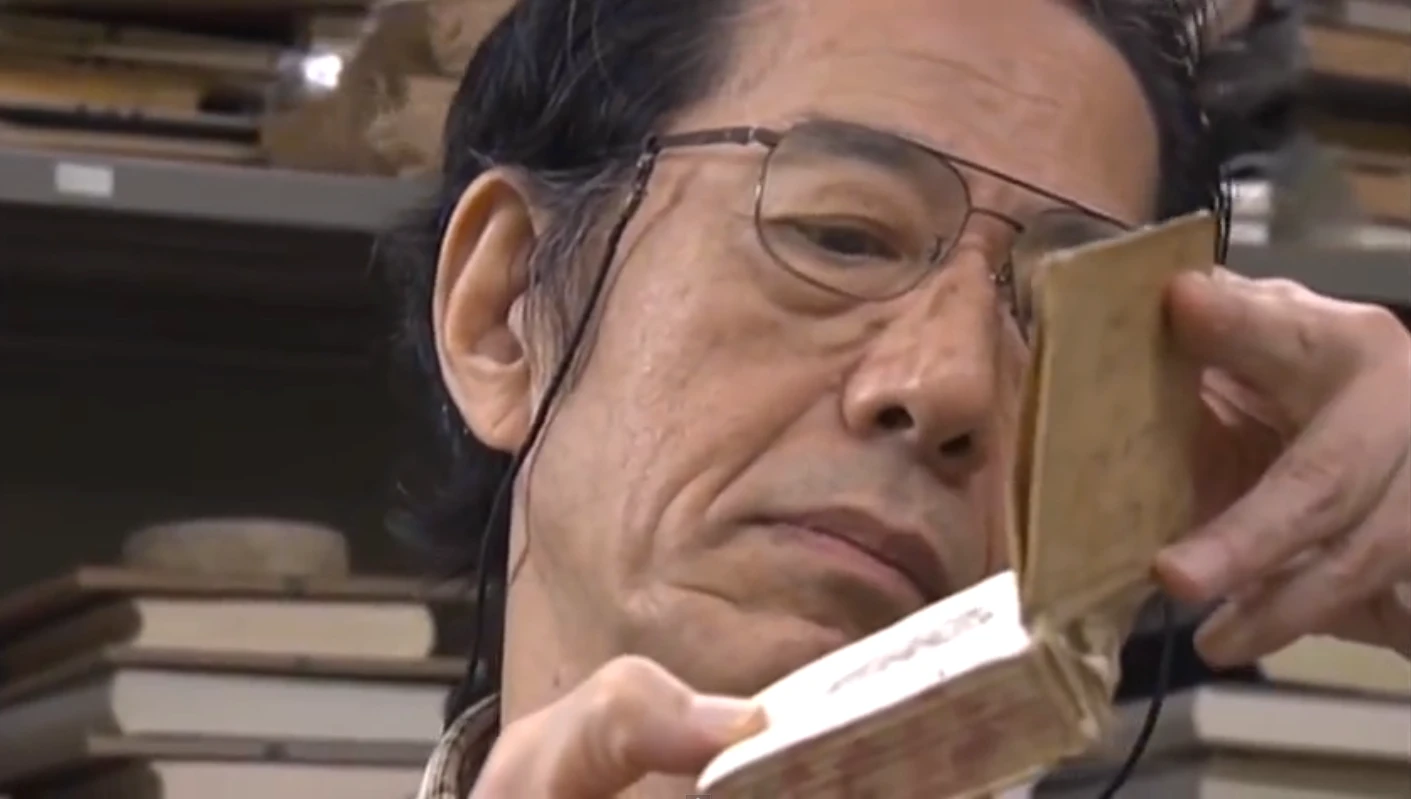

Okano’s work is painstaking. It’s not “glue it back, done.” No, it’s much more delicate, much more precise. Here are some of the steps and tools that blew the internet away.

- Removing old glue from the spine: Okano shaves off or carefully removes deteriorated glue without damaging the backbone of the book. It’s risky. If he slips or snips too much, he’ll jeopardize the integrity of the pages; on the flip side, if he leaves too much, it won’t hold well in the long term.

- Fixing maps and inserts: Maps are often on thinner paper, and Okano often receives them heavily creased. But he doesn’t just flatten them; he glues them onto new sheets, reinforcing weak spots so that they don’t tear any further. Sometimes, he has to accept that the color won’t match perfectly. Part of restoration isn’t making things look brand new, but making them stable and beautiful enough to appreciate.

- Straightening out the corners: This reportedly is one of the most monotonous parts (but also one of the most satisfying). Every page’s corners are unfolded with tweezers, wet slightly, and then ironed flat. Yes, it’s done with a tiny iron. It’s slow work, one page at a time.

- Edge trimming and edge coloring: The edges of many pages have color stains, fading, or unevenness. To fix this, Okano uses a heavy-duty paper cutter to make clean edge cuts and sometimes reapply a faint color or simply clean them. It doesn’t always match exactly, but the key is durability and preventing further damage.

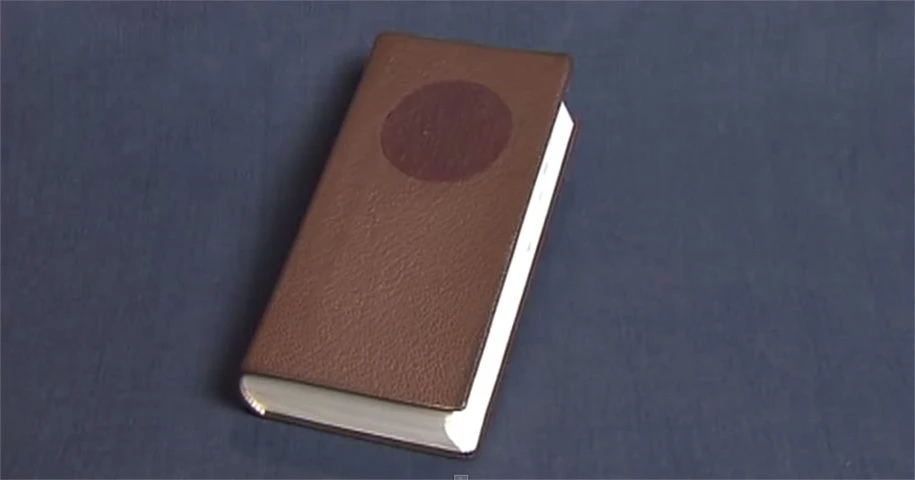

- Restoring or replacing the cover: The front and back covers are often far gone. They bare the bulk of exposure, after all. Okano may preserve whatever can be saved: the title, any original lettering, and decorative elements. If those are too damaged, part of the job is to make a cover that respects the original look and feel, while being robust enough to protect what’s inside.

Why Okano’s Work Matters

Okano’s work helps us hold onto heritage and memories. A book carries more than just text. It carries history. Each page is a memory of who held it, who read it, where it’s been, and what’s marked in the margins. Restoring it isn’t just honoring the words, but the lives that they’ve enriched.

Not only that, but preserving and renewing the books also shows that there’s dignity in decay. Everything ages, pages yellow, glue fails, and binding loosens. But that doesn’t mean the book is worth any less. It’s still just as useful and important as the day it was printed.

The process Okano goes through focuses a lot on the small details. The fold of a corner, the fading of the maps, the wear on the spine. It’s not huge, it’s not flashy. It’s steady, careful, and precise. It’s a refreshing change in a fast-paced and results-focused world. Okano’s work doesn’t just remind us how important our books and memories are, but how useful it can be to just slow down.

Likewise, the work he does takes an incredible amount of patience and skill. Using a tiny tweezer and iron to straighten corners? That’s not a fast job. We could all take a moment to learn as much patience as Okano has.

But it’s more than any of that. We live in a world of disposability: many things are made to be cheap, to be replaced. Books themselves are more often digital or mass-printed, sometimes with little thought toward what happens when they deteriorate. Craftspeople like Okano remind us that objects matter, that wear has value, and that restoration is its own kind of storytelling. They help anchor us in a sense of continuity.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.