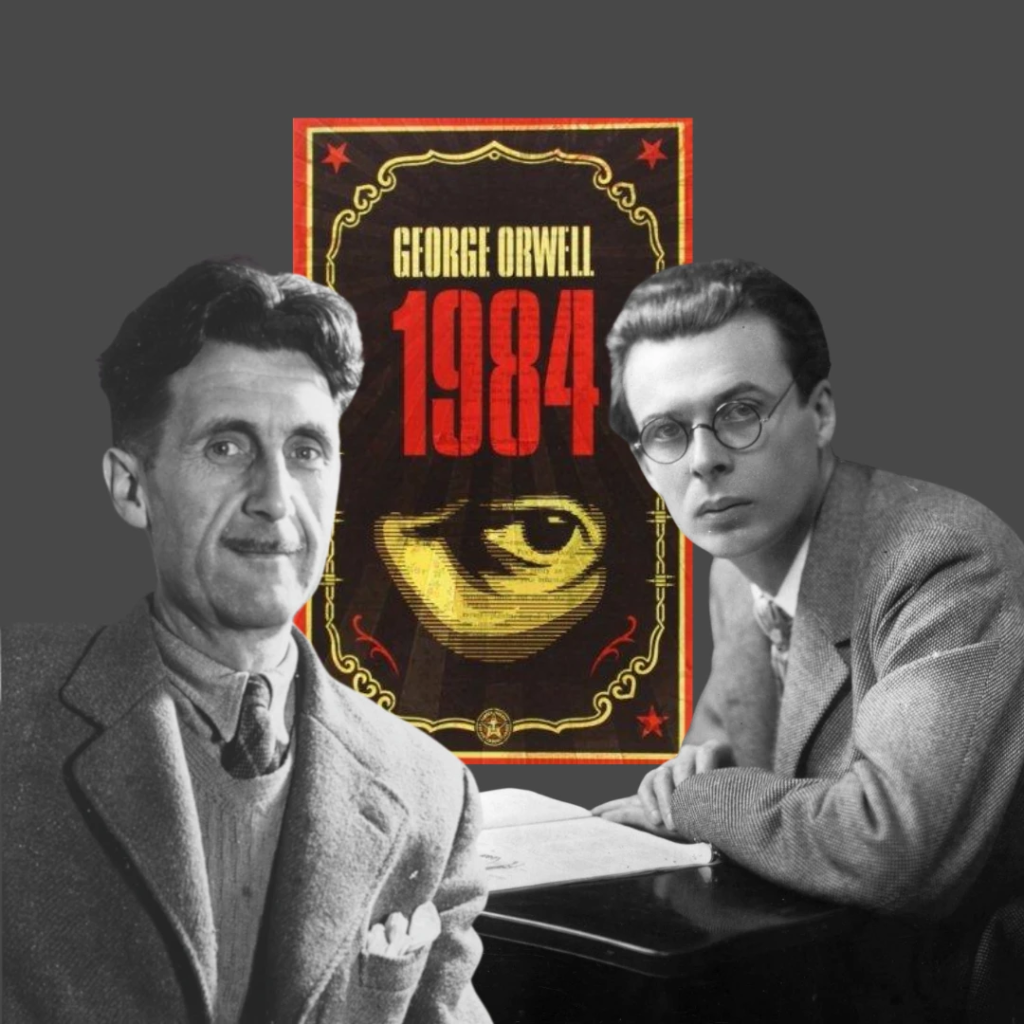

Aldous Huxley and George Orwell each had their own frightening view of the future. Here’s how they disagreed with one another.

Aldous Huxley and George Orwell – two of the titans of 20th Century literature. There are similarities in the work of these two visionaries. Both crafted startling, and even frightening visions of the future, and neither was afraid to confront what they believed to be political realities.

But they did not agree on everything. In a letter from Huxley to Orwell, penned in 1949, their differences in philosophy, politics, and vision, were laid bare.

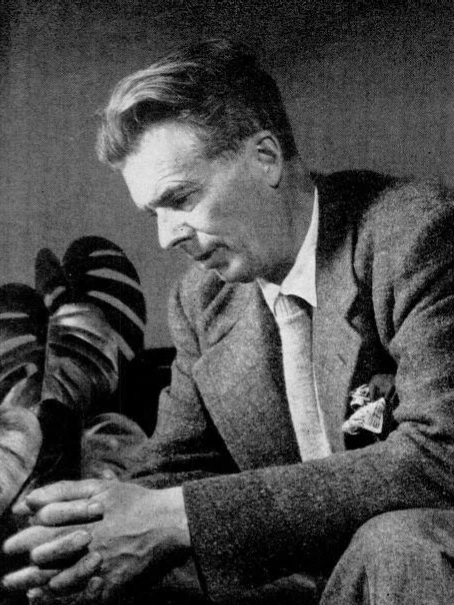

Aldous Huxley and George Orwell – Literary Lives in Parallel

The lives of Huxley and Orwell entwined early on in their mutual careers. Orwell – then known by his birth name, Eric Arthur Blair – first met with Huxley in 1917, aged only 14, while a schoolboy at Eton. Huxley, only 23 himself, had been rejected from the British Army due to his poor eyesight and instead spent part of the war teaching French at the college.

But teaching was not Huxley’s calling. He was already a respected writer and would publish his first novels, Crome Yellow (1921) and Antic Hay (1923), shortly after. It would take Orwell a little longer to find his literary feet, but by 1934 he’d published his own first novel, Burmese Days, and his classic work of non-fiction Down and Out In Paris and London.

By this time, Aldous Huxley had already published the work for which he is best-known. Brave New World was unleashed on the literary scene in February 1932, and made an instant impression on its readers. The work envisaged a frightening totalitarian future, in which the principles of mass-production and homogenisation, made famous by industrialist Henry Ford, would govern society.

In Huxley’s vision, the citizens of The World State exist in a carefully managed system, in which classes and castes are placated and anaesthetised from reality. As a satire of the socialist ideal, and as a warning against the dangers of totalitarianism, Brave New World became an influential text in an increasingly fractured global landscape.

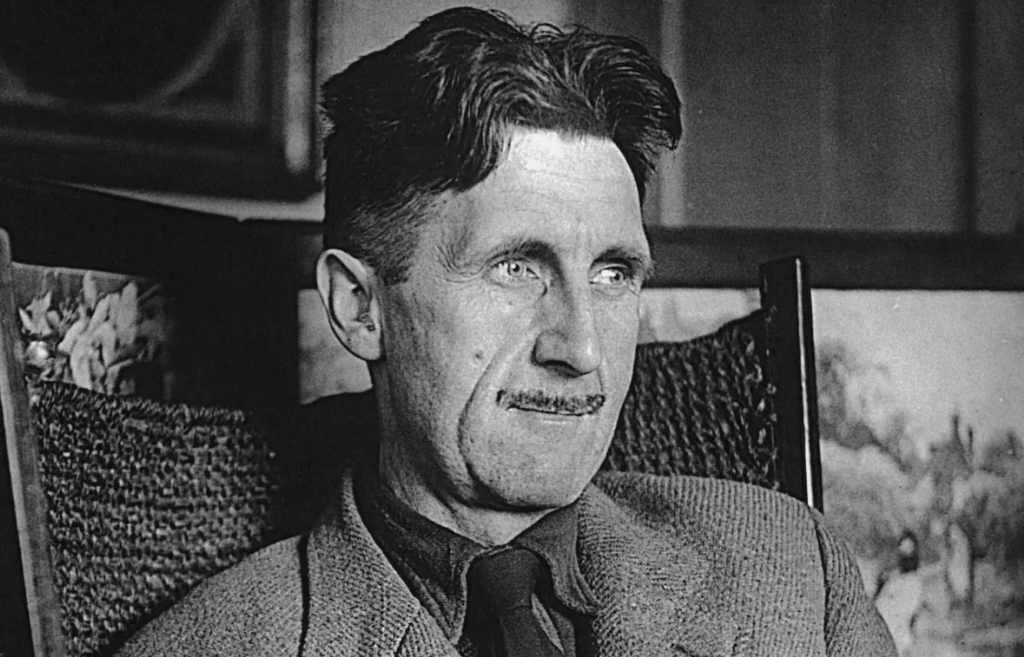

1984 – Orwell’s Own Vision of the Future

The world had been torn apart yet again when, in 1948, George Orwell penned his own vision of the future. This was 1984, and it would be Orwell’s final work.

Undoubtedly influenced by Huxley’s novel from years earlier, Orwell had given his all to this book. It represented the product of his experiences over the last two decades of his life – his time spent examining the polarised antagonism of global political ideology.

Set less than four decades into the future (Brave New World, in contrast, is set around the year 2540), 1984 takes place in Airstrip One – a location formerly known as the United Kingdom. In this world, there are three superstates:

- Oceania – Comprising the Americas, Iceland and Britain, southern Africa, and Australasia.

- Eurasia – Comprising Europe, the Soviet Union, and most of the Middle East.

- Eastasia – Comprising China, East Asia, Central Asia, and much of South East Asia.

Unlike with Brave New World’s warming-bath of distraction and anesthesia, 1984 predicts a violent and repressive system. Visible and omnipresent forces of oppression keep the population in line and maintain the status quo. Just like Huxley did, Orwell draws upon elements of satire, warning contemporary audiences of the dangers of authoritarian fascism and communism. However, the flavor of that authoritarianism is rather different.

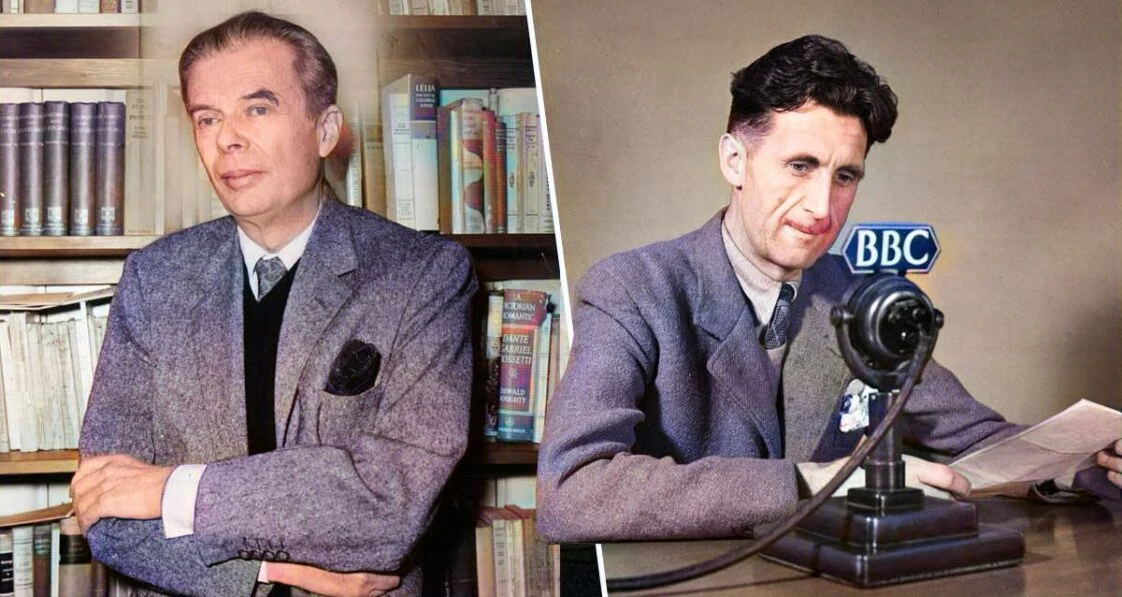

Differing Outlooks, Mutual Respect

Huxley knew Orwell personally, and he’d written his own work of politically-charged speculative fiction that had made him a household name. It’s little surprise, then, that Orwell wanted Huxley’s opinion on the novel.

In October of 1949, Huxley wrote Orwell a letter, outlining his thoughts on the book.

Huxley was quick to praise his former pupil. “I need not tell you,” he said, “how fine and profoundly important the book is”. There was admiration here, and respect too.

But this did not mean Huxley agreed with everything. His main point of contention was in “the philosophy of the ultimate revolution”. Huxley did not see Orwell’s vision as an end-point; more a stepping stone towards something rather different.

“Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful,” Huxley said.

“My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.”

In fact, Huxley believed it may not be necessary for states to utilize repressive force at all.

“Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience,” Huxley continued.

“In other words, I feel that the nightmare of 1984 is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World.”

Enduring Legacies

Orwell and Huxley never claimed to be the same. Both explored diverging avenues of artistry, philosophy, and lifestyle – Huxley was a pacifist, for instance, while Orwell saw action in the anarchist militias during the Spanish Civil War.

But both have left us enduring literary legacies that continue to be pored over to this day. Whether you believe the seeds of Orwell’s Oceania or Huxley’s World State are already being sown, or you prefer to enjoy these novels as works of speculative science fiction, it largely doesn’t matter.

Both men, and both staggering bodies of work, have had an indelible and ongoing impact on global literature, and re-drawn the boundaries of fiction.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.