Explore how one librarian’s love for storytelling turned her Brooklyn apartment into a global hub for Tibetan language and heritage.

For centuries, New York City has been a crossroads of the world, a place where sprawling global networks of trade, migration, culture, and knowledge intersect. Whether setting foot on Ellis Island in the nineteenth century or touching down at JFK in the twenty-first, countless people have arrived in NYC over the last two hundred years, either passing through en route to somewhere else, or settling down.

It’s no wonder that New York has become the most linguistically diverse city on the planet, with around 800 different languages spoken across the five boroughs. Of course, some languages have become more prominent than others, while some remain marginalised. It’s against this backdrop that children’s librarian Tenzin Kalsang is attempting to increase access to her own language and culture – the language and culture of Tibet.

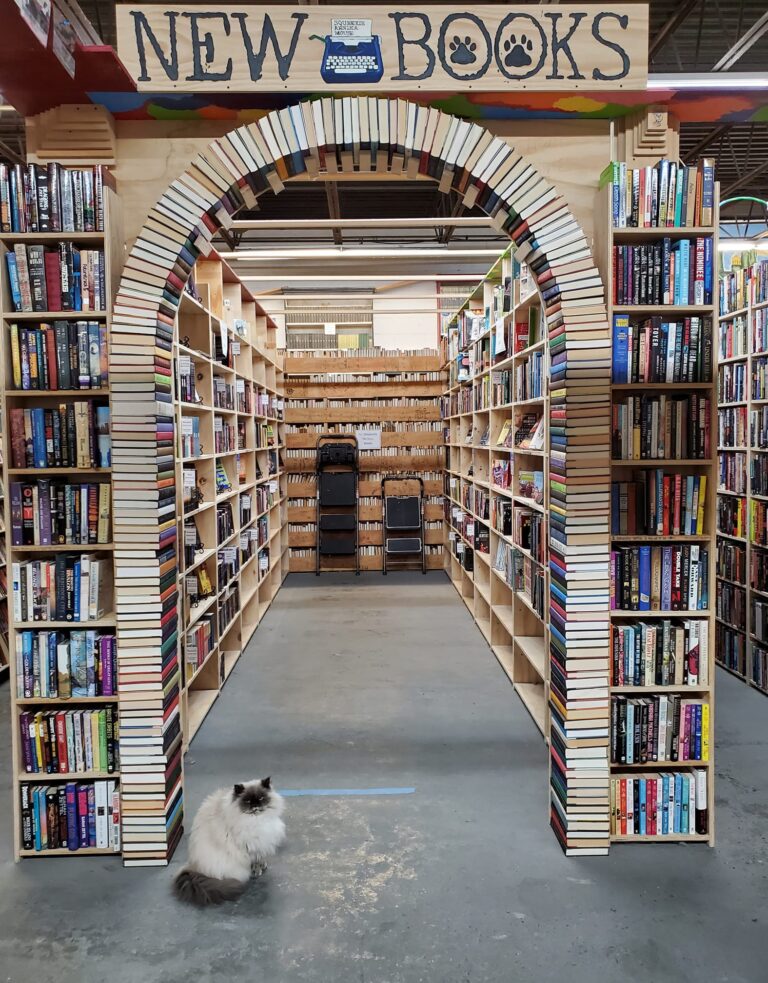

Tibetan Story Sessions in Brooklyn

Tenzin works as a children’s librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library in Williamsburg, NYC. Language and literature have become intrinsic to her professional life, but they are also deeply ingrained in her personal life. As a Tibetan native speaker, far from her ancestral homelands, language is one of the threads that binds Tenzin to her identity and background – and literature is a medium through which this can be expressed.

This was the foundation of Tenzin’s project. As part of her work with the Brooklyn Public Library, she began hosting storytelling sessions, both in Tibetan and in English. She would meet regularly with a group of young residents from the local area, and they would read picture books together, sing songs, and build connections through language.

Even in a city with such a rich linguistic bedrock, a Tibetan storytelling session was unusual. Tenzin’s enthusiasm and eagerness to share and promote her language and culture made these sessions popular in Williamsburg, but the hands of fate and circumstance were about to change everything.

Moving the Project Online

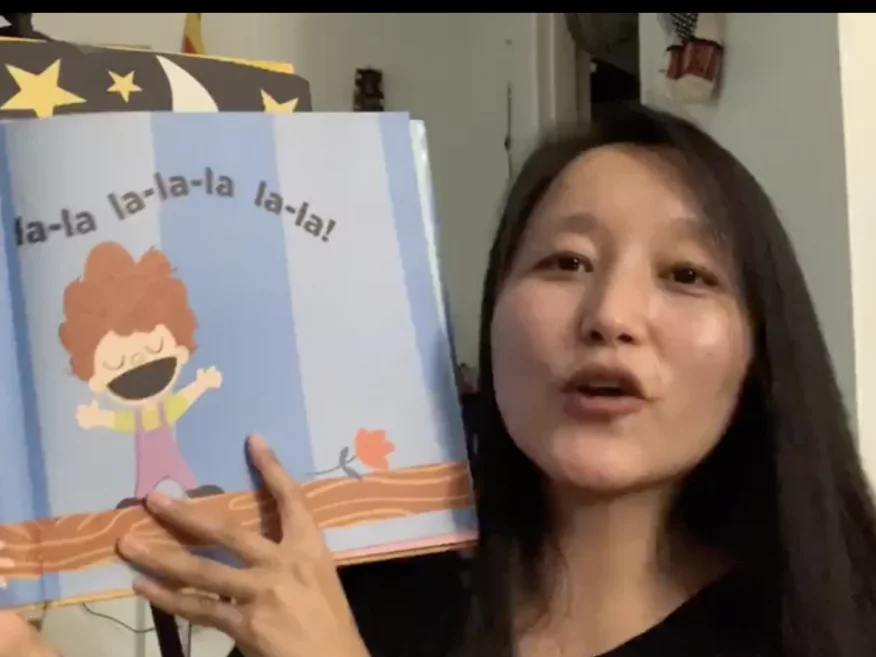

April 2020 was a difficult time for communities right across the world. As COVID-19 put lives at risk and anxiety gripped the globe, physical meetings became impossible. Tenzin’s Tibetan storytime was no exception, and so the in-person sessions were forced to close. Instead, Tenzin did what so many of us did – she used digital technology to take her work online.

Despite her experience as a storyteller and communicator, this new medium made Tenzin nervous. The night before her first online session, she said the anticipation made it difficult to sleep.

“I was like, oh, my goodness, how am I going to do this?” Tenzin remembered. “When I get shy, my face turns really red.”

She needn’t have worried. Her online sessions went down a storm, just as her physical sessions had at the library in Williamsburg. And what’s more, her newfound accessibility meant she was developing a global audience.

From a Brooklyn Apartment, to the World

Tenzin’s storytelling sessions take place in a corner of her apartment, which she has decorated to provide the warm, comfortable, engaging atmosphere she needs to connect with her audience. But that audience is now located across the world.

Within a few months, people began tuning in to Tenzin’s stories from locations around the globe. From Australia to Switzerland, and from the United States to Nepal, viewers logged on to connect with Tenzin and her sessions.

Many of those in attendance were of a Tibetan background themselves, like nine-year-old Tibetan-American Tsojung Yerutsang. But many others were not.

Live sessions were often attended by up to 300 people, and some videos have been downloaded tens of thousands of times. Large numbers of attendees and viewers are people eager to engage with the Tibetan language, even if they themselves do not necessarily have a Tibetan background.

A World in Which No One is Excluded

There are estimated to be around 7.7 million Tibetans across the world. The majority of Tibetans still live in the Tibet Autonomous Region, and in autonomous prefectures on traditional lands in China’s Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces. However, large numbers of Tibetans fled the region following the Chinese annexation in 1950, with tens of thousands settling as refugees in India, Nepal, and the United States.

Disconnected from their homeland, many Tibetans feel that their language and culture are under threat, as each new generation becomes increasingly distanced from their background and ancestry. This is where institutions like libraries can play a unique and valuable role.

“We often say that the library is for everyone, “[but] immigrants and marginalised communities have a hard time accessing and benefiting from library programs,” Tenzin said.

“[People who attend my sessions] see some hope in the preservation and continuation of the language.”

“When I was a child, I didn’t have the opportunity of going to storytime,” she continued. “I model for parents that you can read to your kids in your own language.”

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.