A 19th-century book at Harvard, once covered in human skin, reminds us how far our ethics have come, but also how far they have to go.

It might sound like something straight out of a horror novel, a book bound in human skin, sitting quietly on a university library shelf. But this isn’t fiction. For years, Harvard University held a 19th-century book that was literally wrapped in the preserved skin of a human being.

If you’re just dying to know more, then you’re in the right place.

What Exactly Is “Harvard’s Book Made of Human Skin?”

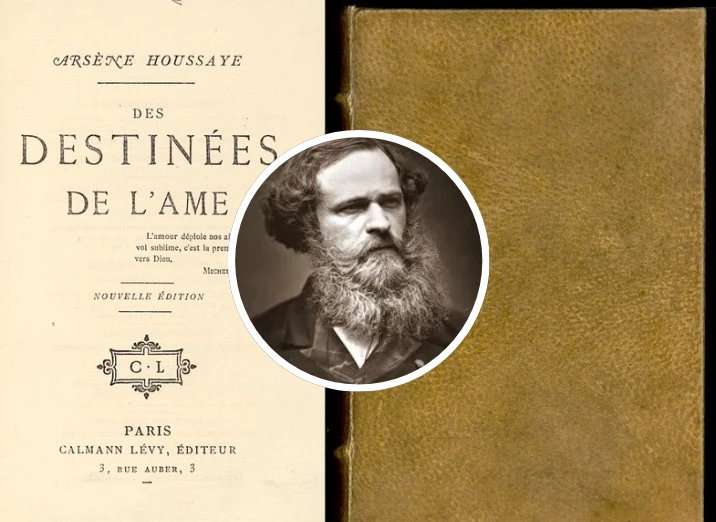

Let’s begin with the basics. The “book made of human skin” refers to a copy of Des destinées de l’âme (in English, Destinies of the Soul), a French meditation on the soul and life after death written by Arsène Houssaye in 1879. Harvard’s particular copy is infamous because, at some point after the printed book was delivered, its owner, a French physician and bibliophile named Ludovic Bouland, decided to bind it using human skin.

Many years later, Harvard eventually acquired the volume, and the revelation of its binding caused a stir. Shockingly, though, this isn’t that unique. It’s an example of a rare (and macabre) historical practice called anthropodermic bibliopegy: binding books in human skin.

Who Was Ludovic Bouland, and What Motivated Him?

Bouland was a medical practitioner and book lover. According to a handwritten note inside the volume (inserted by Bouland himself), he believed that “a book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering.” The note goes further, describing how he prepared the skin for binding, and even suggesting that one could “distinguish the pores of the skin.”

But here’s where things get ethically murky: the skin came from a deceased female patient, likely without her consent, from a psychiatric hospital where Bouland had worked and studied. We don’t know the woman’s name, or whether any relatives were aware or consented (the evidence suggests not).

How Did Harvard Even Come to Own It?

The book was first acquired by John B. Stetson Jr., an alumnus of Harvard. In 1934, he gave it to Harvard on deposit. After that, it moved around: from the general collections to the rare books division, and finally, it became a permanent fixture after being donated as a gift in 1954.

Interestingly, Harvard had long suspected that the book’s binding might be human skin. In 2014, they conducted tests using peptide mass fingerprinting to confirm that the binding was indeed human in origin. That test was fairly definitive, ruling out most other animals and concluding that the sample was extremely likely human.

Harvard’s Reassessment and Removal

Once you realize that a human being’s remains were used, without known consent, and kept in the library collection for decades, you start to see the whole thing as, well… deeply uncomfortable. So how did Harvard confront it?

In the fall of 2022, Harvard’s Steering Committee on Human Remains in University Museum Collections issued a report prompting libraries and museums to examine whether human remains in their holdings should remain under institutional care. Houghton Library then formed a task force, reviewed the provenance, engaged stakeholders (students, faculty, external researchers), and weighed the ethics.

In March 2024, Harvard announced that the human skin binding would be disbound (i.e., removed) and placed in secure, respectful storage. The library concluded that the human remains “no longer belong in the Harvard Library collections,” given the ethically fraught nature of how they were obtained and the ongoing question of dignity to the person whose skin it was.

Harvard also acknowledged mistakes: historically, the library handled the book in ways that treated it as a curiosity or a museum oddity, rather than centering the humanity of the person involved.

Respectful Disposition and Ongoing Research

The removed skin is currently in secure storage while Harvard and relevant French authorities undertake further provenance and biographical research. The goal is to learn who the anonymous woman was, under what circumstances the skin was taken, and how best to provide a respectful disposition. Additionally, the university is consulting with stakeholders in France (where the act likely occurred) to determine how to lay the remains to rest, perhaps through reburial or another culturally respectful treatment.

Meanwhile, the text block of Des destinées de l’âme (i.e., the pages, minus the binding) is now separate, and while the book is temporarily unavailable for in-person access, researchers can still access the digital scans via Harvard’s online system.

The Intersection of Medicine, Ethics, Libraries, and Human Remains

This book highlights a rarely discussed (and very niche) overlap: libraries, as custodians of artifacts, sometimes hold human remains (bones, tissue, hair), especially in medical or anthropological collections. Decisions about how to care for, display, hide, or remove them often involve moral, historical, cultural, and legal judgments. The Harvard bookcase shows examples of what happens when this need arises.

It also illustrates how the medical community in previous centuries sometimes treated bodies as raw “material” rather than dignified persons. The woman whose skin was used was not accounted for in history; her remains were reduced to a binding. That reduction is exactly what many modern ethical reviews aim to undo, and what Harvard is actively pushing for in this case.

The Limits of “Curiosity” and “Collection”

Many older museums and libraries accumulated strange or grotesque items under the banner of “curiosity” or “scientific interest.” But it seems that, over time, shifting norms are forcing these institutions to reconsider: was collecting justified? Who is or has been harmed? What is dignity owed to the dead?

Other Examples of Anthropodermic Binding

Harvard’s book is not the only known case of anthropodermic binding. But it is now one of the most visible, partly due to Harvard’s prominence. Some previously suspected human-bound books have later been found to be animal leather (sheep or goat) upon scientific analysis. If you’re interested in this tradition, check out Dark Archives, a book by Megan Rosenbloom that examines the phenomenon, what it reveals about medicine and death, and the ethics of keeping the books all these years later.

Harvard University is certainly not alone in its possession of such books. The Wellcome Library in London once held several suspected human-skin bindings, though scientific testing later proved some were made of sheep or goat leather. The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia has a verified human-skin-bound book titled The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen, which Allen himself reportedly requested be bound in his own skin after his death. The Brown University John Hay Library also possesses a confirmed human-skin-bound volume of Practicarum Quaestionum Circa Leges Regias Hispaniae, a legal text from the 1600s.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.