Discover the extraordinary story of Helen Fagin, a 100-year-old Holocaust survivor, who proved that in the darkest times, stories can be lifelines.

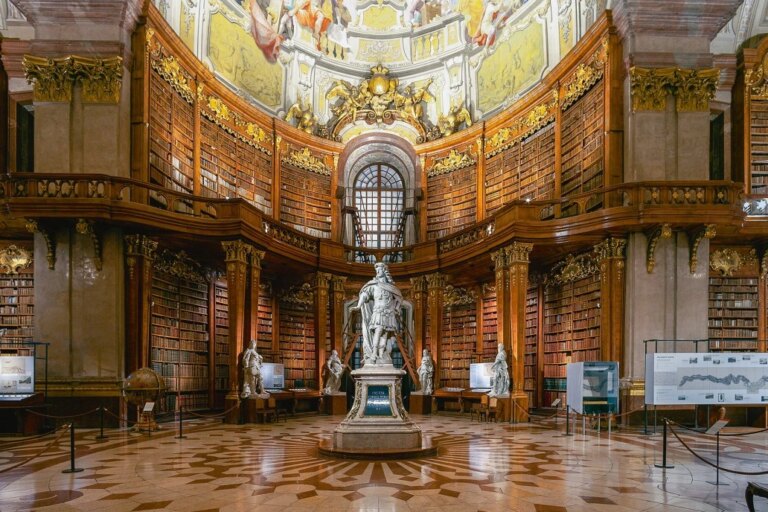

For most of us, reading is a pastime. A way to learn, escape, or unwind at the end of the day. But for those trapped in the ghettos of Nazi-occupied Poland, books became something else entirely: a fragile lifeline, a reminder of humanity, and sometimes, the only spark of hope left in a world of despair.

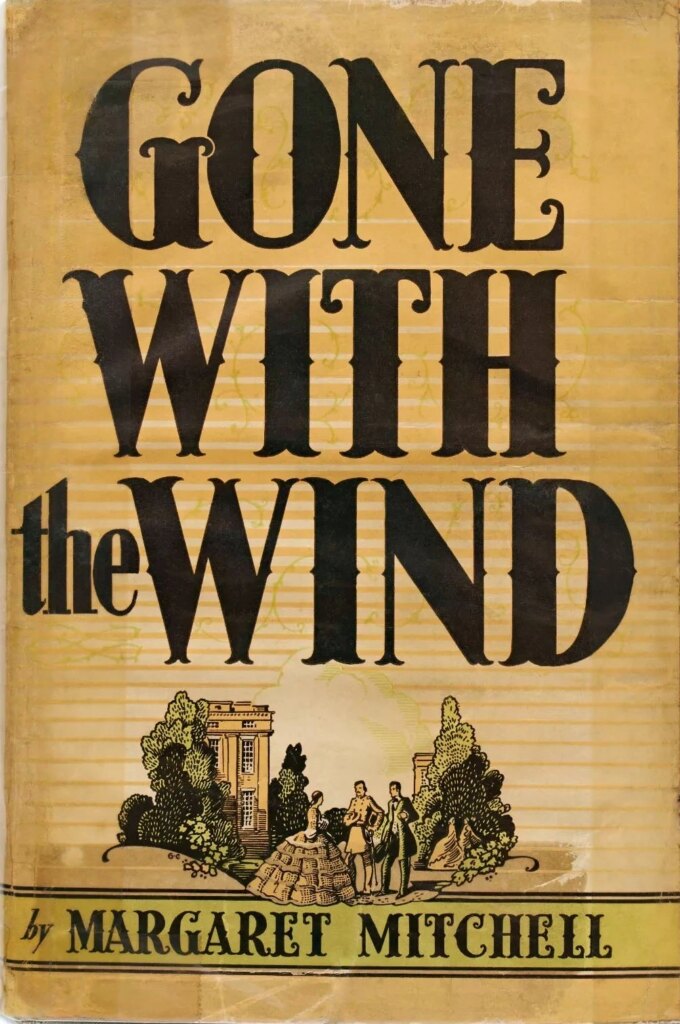

This is the story of Helen Fagin, a young woman who used a smuggled copy of Gone with the Wind to keep the flame of imagination alive for a group of Jewish children, at a time when survival itself seemed impossible.

A Classroom in the Shadows

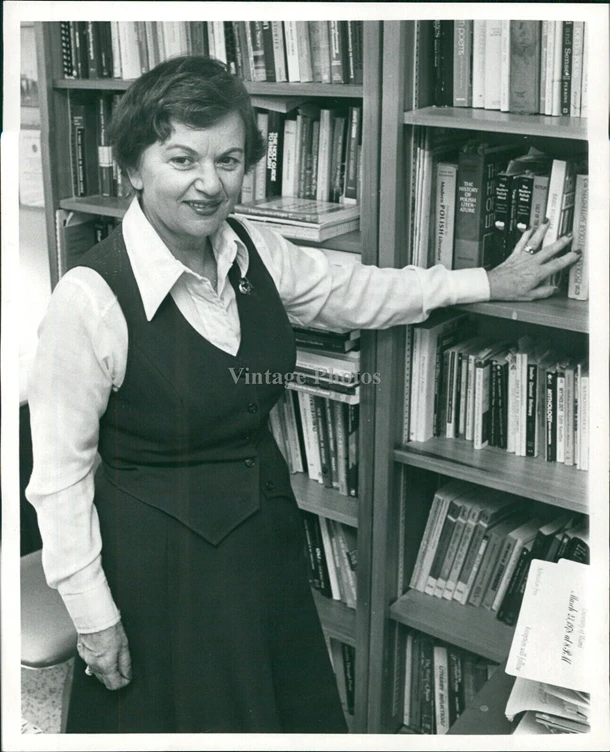

Helen was just 21 when she and her family were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. Education was forbidden, books tightly controlled, and being caught with the wrong text could mean brutal punishment or worse.

Still, Helen believed the children around her deserved more than silence and fear. So she created a secret school, hidden away from Nazi eyes. At first, she taught the basics: Mathematics, Latin, and whatever scraps of knowledge she could safely share. But soon she realized something deeper was missing. She realized they didn’t only need lessons but hope, the kind that only stories could give.

Smuggling a Dream

Through an underground network, a few trusted families managed to pass books hand to hand under the cover of night. Each reader had only one evening with a book before it had to move on, reducing the risk of discovery.

One night, Helen got her turn with Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. She devoured it from dusk till dawn, swept up in the loves and betrayals of Rhett Butler, Scarlett O’Hara, Ashley, and Melanie.

The next day, when one of her students whispered, “Please, tell us a book,” Helen knew exactly what to do.

For that one forbidden hour, she retold the story from memory. In that cramped secret room, Scarlett’s sharp tongue and Melanie’s quiet grace came alive. The children’s faces glowed, their fear momentarily replaced with wonder. They weren’t starving, hunted teenagers in a ghetto anymore.

They were travelers in another world, a world with parties, manners, and hope. As they slipped away afterward, one green-eyed girl turned back with tears in her eyes: “Thank you for this journey into another world. Could we please do it again soon?”

Loss and Survival

The ghetto tightened its grip. Raids grew more violent. One by one, many of Helen’s pupils were lost to the Nazi machinery of death. Of the 22 children who once gathered in that hidden classroom, only four would survive the war.

But the green-eyed girl who had clung to Scarlett and Melanie’s story was among them. Years later, in New York, Helen found her again. Grown, married, alive against all odds, she introduced Helen to her husband with words that have stayed with her ever since: “This is the woman who gave me hope and dreams when I had none.”

A Legacy of Reading

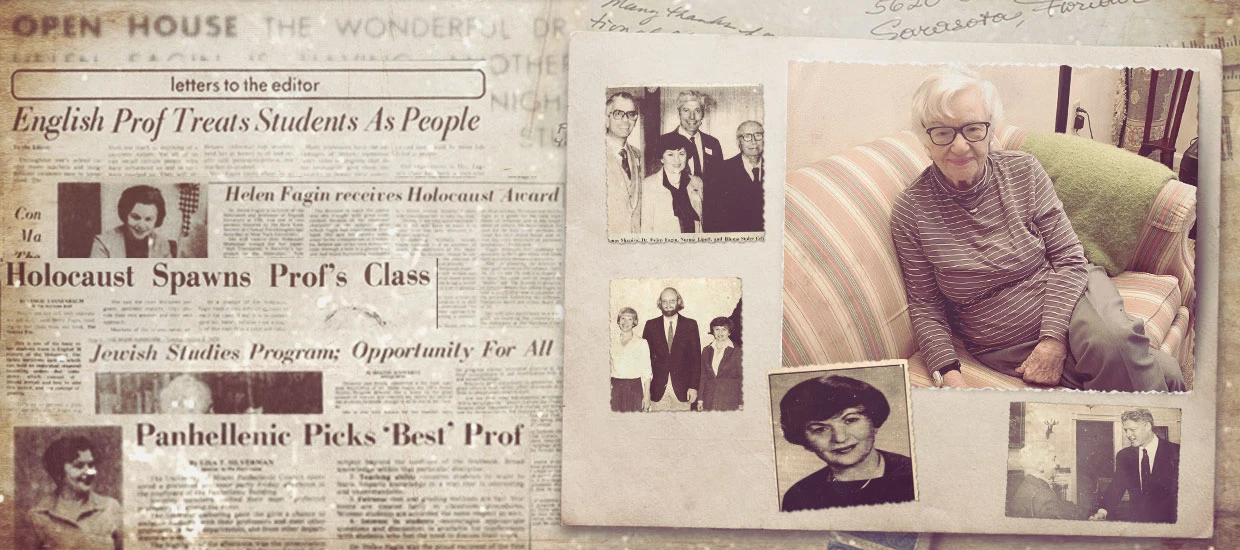

Helen Fagin went on to escape Europe, build a new life in America, earn her doctorate, and teach literature for decades. She became a fierce guardian of memory, helping to establish the Holocaust Memorial in Washington, D.C., and sharing her testimony so that the world would not forget.

Even into her nineties and beyond, she remained a voracious reader — moving seamlessly from Whitman to Camus, always hungry for the kind of truths that only stories can give.

Her letter about that secret classroom eventually appeared in A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader, alongside contributions from Jane Goodall, Neil Gaiman, Judy Blume, and other luminaries.

But perhaps no letter in that collection carried the same weight of lived truth as Helen’s. Because Helen knew, better than most, that a story can do more than entertain or educate. It can preserve humanity itself.

Join our community of 1.5M readers

Like this story? You'll love our free weekly magazine.